the spiritual practice of knowing the risks and loving anyway

an interview with Stephanie Duncan Smith

Today it is my pleasure to welcome author

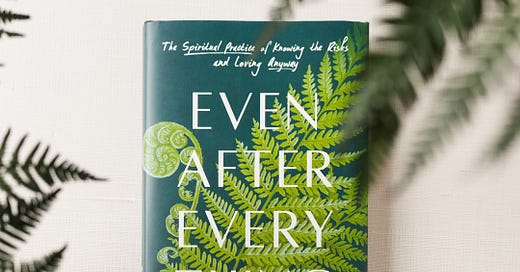

to the pages of The Rewilded Life. Stephanie helms my favorite Substack on the craft of writing, Slant Letter, and this week launches her first book into the world. Below, she answers all my burning questions about Even After Everything: The Spiritual Practice of Knowing the Risks and Loving Anyway.Please give a warm welcome to Stephanie, and feel free to ask questions of your own in the comments!

Your book might seem to readers like a memoir about grief related to pregnancy loss and the changes that accompany becoming a mother, but at the heart of the book is something else: that our lives are lived in seasons, and that sometimes the story of faith we hear at church and in its seasons can feel contradictory to our lives. Will you say more about why it matters to recognize that our lives are “seasonal” and why it’s OK for us to feel out of sync with the church sometimes?

Thank you for recognizing that! This book was always meant to be for anyone feeling the pull of playing it safe against the risks of love and getting hurt. I also wrote it with a special care for those who have experienced this particular loss.

When you’re in the midst of a personal winter, a personal Good Friday, seeing spring in full-blast and hearing Easter alleluias or the triumphs of others can be deeply painful, because it makes us feel unseen. This dissonance can feel incredibly isolating.

But this is what I love most about the liturgical year: it’s a full circle, life to death to resurrection, and this circle holds space for the full spectrum of the human experience. Its range assures us that there is no personal moment we could experience that does not belong. And because God stands outside of time, there is no moment in which the God who became human, cried why, and now lives with scars cannot meet us.

More than anything, the Incarnation reveals a God who never makes light of our pain. If that means skipping out on a service or tradition or gathering, or going dark for a while, do that and know you are held right where you are.

You write about the liturgical year as a circle of time that ultimately points to being held by God at every moment of life. What can readers expect to learn about the seasons of the church year and the spiritual life?

I write it this way: “From Advent to Ordinary Time, the liturgical year cycles through deeply human themes of love, risk, great joy, dark nights, uncertain in-betweens, and new beginnings. I began to read this mirroring as divine empathy… And in this empathy, I began to find the consolation that we are seen and may even be steadied by a love that stays with us through it all.”

I love the image of the sacred year as a circle and think of it almost as a color wheel of emotional experiences. If you think about it this way, every encounter of personal moment with sacred time is unrepeatable, wholly original, as the God of empathy meets us in our here and now.

The experience of grief you describe in the book carries you to unexpected spiritual places, like confronting masculine concepts of God. Can you say more about how the storms of life can batter and reshape in meaningful ways our theology, our faith practices, and our relationships with spiritual communities?

I have a friend who refers to his spiritual direction as couples counseling with God, and for me, it sometimes feels like that. When we lost our first pregnancy the week before Advent, during Advent’s week of joy, I experienced one of the greatest rifts of my life with God. In the book, I write that rift, and I don’t hold back.

But I also write the rediscovery of God as a mother who rushes to be present with us in our pain, God as a womb who holds all things together when we cannot do so on our own, and Advent not as a twinkle-lit season of cheer but a season of a world crying out for help to come.

I had to work all this out for myself and there were no short-cuts. But anytime we can honestly engage the rift, I believe we’ll make honest discoveries, and through that reckoning process, we’ll own them for life.

I also believe that the healing we need most is supported in community, but we will need to discern what is a safe community—who will be willing to sit with us in our pain without prescription, without papering it over.

One of the themes in the book that is most palpable is the tension between having individual agency and control over one’s life and the need to accept the pains and out of control events of life that change us. As you wrote this book, how did the act of writing fit into that dynamic?

It’s called a book release for a reason! In writing as in life, all you can do is show up to what’s yours to do, and release the rest. This book has been five years in the making, in the living. I wrote it through four pregnancies, two losses and two newborn eras, and I wrote it with the meticulosity of a poet composing a seven-line poem. When I write, it’s tunnel vision—all focus, all creative control. And now I release it to a life of its own as it engages the lives of its readers, creating an entirely original conversation one-to-one with every single reading experience. That loss of control could be terrifying (and sometimes it is), but I prefer to think of the letting go as an offering, a gift.

One of the first things people will notice when they read your book is that, even though it’s written in sentences, you bring the voice of a poet to the page. What does that lyrical writing style bring to the material that wouldn’t be there otherwise?

Poetry has a way of helping us practice presence—its vividness enlivens our senses and focuses our scattered attentions. I love that you observe the poetry of this book because this was by design: I wanted the reading experience to feel vivid, enlivened, and ultimately, to invite readers into the peace of the exhale after reading a poem that satisfies.

Additionally, as an editor, I study what resonates with readers, and what readers underline. So I started with the end hope, and wrote backwards—every underline earned will be, I hope, a gift the reader can carry with them from the page into their present.

You’ve been editing other people’s writing for years, and this is your first book—congratulations! Now that you’ve written a book and gone through an editing process, how has it changed your editing work and the writing you continue to do?

I have always had great respect for the work authors do, but I have never done what I have tasked them to do—until now. I have never written nor promoted a book-length work before. Doing so now has given me newfound reserves of respect and empathy for authors in this public work, and this has been making me a better editor from the beginning. Specifically, I feel more insistent than ever in celebrating the highs and the joys in the process where you encounter them. Every creative work deserves that.

Who did you write this book for? What do you hope it will do for the people who read it?

This book is for everyone who has felt the tension between hoping for the best, and fearing the worst. It’s for anyone who feels torn between trying again, hoping again, loving again, and playing it safe. It’s for anyone who is searching for steadiness amid the dissonance of life’s joy and sorrow, love and loss. And it’s for people, like me, who cannot stomach any kind of spirituality that overpromises, so you won’t find that here. Rather, this book is an offering of something steady, something true, a rhythm you can trust, a love that can hold you, when everything else is shaking.

“But this is what I love most about the liturgical year: it’s a full circle, life to death to resurrection, and this circle holds space for the full spectrum of the human experience.” So beautiful. So looking forward to reading and sharing this book. 💚🙏

wow, this book sounds amazing and timely, thanks for the thoughtful interview!