You may (likely) or may not (who knows) have heard that on a recent episode of the Call Her Daddy podcast, 27 year-old pop star Chappell Roan offhandedly commented, “All of my friends who have kids are in hell. I don't know anyone who's happy and has children at this age. I’ve literally not met anyone who’s happy, anyone who has light in their eyes, who has slept.”

The internet then did what the internet does: lost its mind and promptly divided itself into impermeable camps. (Just two, obviously, because who has time for nuance when there are opinions to air?!) Honestly, the whole thing bored me and I wasn’t going to comment on it at all, but then yesterday as I drove home after school drop off, happily belting out the salacious lyrics of The Rise and Fall of a Midwest Princess as it blared from my bright blue minivan, it struck me that I actually had something worthwhile (if belated) to add to the conversation.

First, let’s be clear: I am a big fan of the Midwest Princess. I’ve seen her in concert, and I’ve even written about her here. I love her creativity, her lewks, her boundaried relationship to celebrity, and the way she’s elevated cultural discourse on female pleasure. If I were having drinks with Chappell Roan I’d talk about all those things, but maybe especially the last, because I’d want to tell her what I’ve realized after all these years of being both a mom and a sexual person:

Mothering is itself a powerful conduit of female pleasure.

That this statement sounds far-fetched (or pitiably delusional) is proof of the insufficiencies of the modern feminist movement, the same movement that Chappell Roan’s entire career rebukes for its performance of empowerment but rigid lines of exclusion. In mainstream feminism, the idea that a woman might derive physical, spiritual, and, yes, even intellectual pleasure from motherhood is as rejected as the legitimacy of trans women’s rights or Black women’s quest for liberation. We all deserve better.

I’m not spinning tradwife apologetics over here. (Though if that lifestyle makes a woman truly happy AND she’s doing no harm to others, I’m all for it.) I write as a mom who deeply despises cooking, appointment making, cleaning, library book returning, and basically all the parts of parenthood that someone with ADHD is very likely to hate. But I also write as a mom — a tattooed, pierced, liberal, working, usually braless and cursing mom — who absolutely loves being a mom. Who sleeps with her kids because it’s her preference. Who takes baths with them until they stop asking her to. Who dyes her kids’ hair because it’s fun. Who has taken both daughter and sons to the nail salon. Who buys extra concert tickets so they can come along. Who might hate board games but is always down for a hike in search of a cool new bone or feather.

Don’t get me wrong, being a parent is hard. It’s really freaking hard. As much as I adore my children, there are some days when the logistics of raising them has me asking why I did this to myself. No one should take on motherhood unless they truly want to, and I applaud any woman who bucks social expectations and stands firm in her own certainty that raising kids is not for her. But for those of us who are moms, there is a certain pleasure that makes the challenges and exhaustion worth it but that is difficult to explain to someone else. So it’s easy to see why, to an outside observer, it would look like a really rough gig.

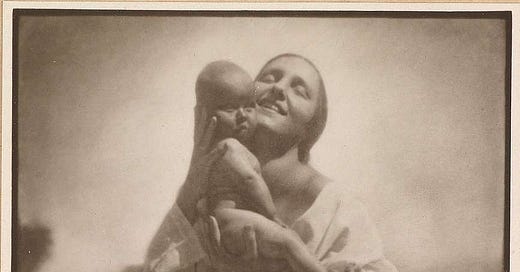

Meanwhile, on the inside, we’re indulging in yummy little biological treats like oxytocin. Oxytocin, known as “the love hormone,” is released during sexual arousal and orgasm. But guess what? It’s also released during and after childbirth (did you know that it’s even possible to orgasm while giving birth?), during breastfeeding, and throughout the parent-child relationship, but especially in the demanding infant and toddler years. Holding your sleeping child or locking eyes with your baby while nursing might not have the shazam of an orgasm, but chemically, it’s pretty on par. Our brains receive a flood of happiness, connection, and sense of purpose — one that is scientifically measurable.

But there’s more; and the “more” is less measurable and harder to articulate. This more is the intense new awareness of human (and nonhuman) interconnection that could well be described as a spiritual awakening. This more is the awe of finding yourself capable of putting someone’s life before your own. This more is the adventure of meaning-making, and even personhood-making. This more is the fearsome responsibility of unfolding the world before a brand new creature. The felt sacredness of these realities is a real, experiential, formative means of female pleasure.

Off the top of my head, I can think of a handful of possible reasons why women find this pleasure hard to describe (case in point, a considerable percentage of time spent on this essay has involved me helplessly staring into space). American society does little to support families — especially mothers — economically, logistically, mentally, or medically, making parenthood inordinately stressful. Serious artistic inquiry and scientific research have only fairly recently begun devoting time and money to studying motherhood; we’ve had a deficit of symbols and language to draw from. What’s more, the legacy of boomer-era feminism has made it a faux pax to like motherhood too much. Why spend time trying to describe a joy you are told is inferior to other joys?

But there is a difference between a challenge and an impossibility, and more and more, I think it matters that we try. I think it matters that I tell you that for all the ways mothering sucks the life out of me, it also breathes it back a hundredfold. I think it matters that I tell you that my children’s companionship has pulled me from the brink of darkness, unbeknownst to them. I think it matters that I tell you that when one of my children reaches for my hand in a store, or cracks a joke that makes me cackle, or dances with me in the kitchen, my soul is, just for a moment, relieved of the burden of being human in this harsh world; just for a moment asked to hold nothing but the pleasure of loving and being loved.

I have long thought that part of the problem with trying to describe the pleasures of motherhood is that we don't have adequate ways to talk about bodies that aren't sexualized. There is this exquisite joy that comes with the proximity and intimacy that parenting brings - the touch, sound, smell, sight, feel of caring for another small, tender, growing body and mind and soul - but how can we express this without sounding weird or creepy? But watching them growing, just beholding them at all, let alone the absolute transformation involved if we get to bear and birth and nurse them - it has utterly turned my world upside down and I struggle to put it into words. Thank you for wrestling with the ineffable. We need more of this, because I fear that we are haven't adequately conveyed the heights as well as the depths of what mothering means.

This deserves to be a book.